Moving on - or BACK - from the present. Stories about travelling with Marjan, a la the Steinbeck book wherein I am the dog. At Substack, also posted at Instagram.

Fights Wkly 2024 03

Fights Wkly 2024 02

Fights Wkly 2024 01

Bruce Cockburn's Smooth Revolution (from misterjep.substack.com) →

Welcome to the several recent signups to this newsletter! I hope you enjoy whatever this is. If you’re new or confused or anything: this is a newsletter/comic strip about the 1980s, specifically my life during it (ages 10-19), and the music that happened then. It wanders a lot: sometimes it is also about a spaceship/submarine driven by three avatars for myself – a mouse and a ball and a robot – who sit in the WKRP DJ booth. Sometimes they take listener calls; other times, they just wander around being moody. I don’t plan much.

The first year of this newsletter was weekly – that has shifted to every two weeks since January as I’ve added other writing projects to my roster.

Currently, the focus of the strip is Jobs I Have Had. This will likely (soon) pull us into the 1990s! I’m not sure what’ll happen with that. I don’t want to change the strip’s name, and I have not touched upon plenty of 80s bands I want to include. What will happen? Ahhh!

Okay, Move On

I am 17 years old in today’s strip, back in Sarnia, living with my dad, post-his-divorce, getting a job at Nabor’s, which was a low-end department store akin to the old BiWay. I thought I’d have a ton to share about it, but it only wound up needing three panels. Radio, RadioI have only one musical memory from Nabor’s: they always played CHOK in the store, which was one of the two local FM stations. CHOK played easy, familiar music, and since this was before the days of New Country and Smooth Jazz, it was Pop, minus anything very challenging.

As an aside, just after I’d moved to Toronto, my brother landed a job as a DJ at CHOK, which I loved. When I’d drive back to visit with a friend, we’d savour the moment when we could start to pick up CHOK on the radio and, if we were lucky, hear Jim telling people how to get tickets for a big turkey giveaway while introducing John Cougar Mellencamp.

Here’s the tiny little story, though: one day while refolding T-shirts, I heard a song by Bruce Cockburn and was smitten. However, the DJ didn’t announce the title (or I didn’t hear it), and so when I went to buy the song, I had to sort of hope that Cockburn’s latest single was the song I’d heard. It was not. I had heard “Tokyo” for the first time on the radio; I bought the boring “new track” from his hits record, called “Waiting for a Miracle.” I still possess that 45, and I still quietly resent it. Such drama!

Bruce Cockburn

When I was learning about music, Bruce Cockburn was always around (he’s still around) in Canada. He was a guitarist and singer/songwriter who’d started off folkie but moved towards a more electric rock sound. To be honest, I haven’t paid much attention the last 30 years, so I won’t pretend to know a ton. I just learned he’s released 34 records.

But in the era I paid attention to, from the late 70s to the late 80s, he took complicated situations and distilled them so that his listeners could learn. He sang about Guatemalan refugees, the International Monetary Fund, and government covert activities, and then I had to go learn what those all were. He’s the first person who told me Canada was on stolen land. Only Billy Bragg gave me as much (useful) homework.

He also sang so sweetly about Toronto – “Coldest Night of the Year” and “You Pay Your Money and You Take Your Chance” were basically what my anticipations of the city were based on before I arrived. He’s a great lyricist, weaving short stories out of sweet images:

Woman cry, chase man down street, crying

No, Chuckie, no, please don't

Another girl comes, they run along St. Andrew,

Turn south on KensingtonMeanwhile, Chuckie beats it down the alley by the chicken packer’s

By the time I reach the corner, they’ve all vanished -

Just a deaf kid talking like Popeye

To a large fleshy laughing man in a blue shirt

–“You Pay Your Money and You Take Your Chance” (1981)

Like a few of his contemporaries – Paul Simon, Peter Gabriel, and David Byrne come to mind – he was interested in and incorporated musical traditions from other countries. It wasn’t seen as colonial appropriation back then; it was contrarily kind of adventurous and brave, and educated us about more musical options than the radio or school would. It’s seen differently now, and I get it. But I think you can subsume that issue under this: music is inherently about sharing. Sadly, the music industry is about selling, and way too often, stealing. This will always be a tension.

I’ve mentioned Bruce Cockburn here before – when Marjan located the late-80s clean studio style of production in Suzanne Vega’s Solitude Standing as also being the Cockburn sound. Darlings, that is it for now. Thanks for reading. If you dig it, please share it.

love

jep

Film School! (from A Different Fish)

Dear Readerpeople (including recent signups – welcome, and thanks)!

I’m sorry to have been writing so little this month. All is well – I try and go with the flow when it comes to creative energy, and not sweat the cycles, but that is not to say I don’t fret about it here and there. Right now, I’m a bit worried about what happens when I return to the classroom grind. Historically my written output has dried right up; who wants to sit at the computer and write about the job you just did all day?

But I do have a thing I will really want to share as it goes along, in whatever form that can take.

I’m about to launch a new project at my school: I’ve proposed to the bosses, who have welcomed the idea, a school-wide film education initiative. Over the next couple of years, we hope to incorporate film studies into each grade, from the youngest students to the seniors (my school runs from kindergarten to grade 12). I have plenty of ideas and will be launching it (gently) within the month. I’m really excited.

Yeah, But Why?

I started incorporating film in my middle school classrooms way back in the day (last century!), and started teaching grade 11 and 12 film courses about a decade ago. My takeaway every time has been that students really dig it, and more importantly, are really GOOD at it. It makes sense: kids are consuming “movies” from their earliest years onward – on phones, TV, theatres, screens on the subway, commercials, social media, etc.

They’re interested, too: take a picture of a little kid and see if they don’t ask to see it.But they’re really not taught about it in school – at least not well and not often. Their teachers usually have little to no film education. When film is used (i.e., showing movies or YouTube videos), it is used at a simple level: show it all, then talk about it. That’s not a criticism; adding new things to schools takes time. I’m fortunate to work at a tiny school that can pivot, try new things, and explore. If it goes as I imagine, we’ll be able to demonstrate a clear and usable model for educators in other schools.

I’m also very lucky to live in a major film city, where opportunities are bountiful. My little school has sent lots of students on to film school/film work over the years we’ve been teaching film. I can only imagine the impact of 12 years of film education: lots of what I’m teaching at the senior levels could be taught much earlier, and then the senior classes could be more specialized and robust.

Media Literacy

Atop the other reasons to implement real, informed film education is a desperately needed side effect: a population educated in the workings and impact of film will be more savvy and less prone to being suckered by political leaders or marketers and whoever else preys on naïveté. It is at least worth an experiment, for sure. So: even when I cannot summon long articles during the school year, I will share the experience(s) here, and the ideas, and the results, and anything else I can. Sometimes that might look like journal entries – we’ll see.

As always – and I really MEAN this – I love to hear impressions, extensions, and oppositions to the ideas I explore here. I dig working collaboratively, and know that solo ideas are often weaker. I am excited to be partnering with colleagues and figuring out the shape of this program. If you have thoughts, please share. If you like any ideas, take them wherever you want.

More soon. Thanks for reading.

XO jep

Changes to Childhood Affect Attention (from A Different Fish)

Sorry for the silence – I have been in a not-unpleasant stupor since getting back to Toronto and home and my usual life. It’s been lovely, but I have not typed more than nine words till now.

cover of Stolen Focus by Johann Hari

I just wanted to share this excerpt from an older (Feb. 11, 2022) Ezra Klein Show. Ezra interviews Johann Hari, whose Lost Connections book about loneliness I really enjoyed, and whose new book Stolen Focus is about attention. Towards the end of the interview he describes school as a perfect machine for ruining attention. I share the text from the transcript here.

Ezra Klein: So you said something interesting, which is that if you wanted to design an education system to wreck people’s attention, you would design this one. How so, and as my final question before books to you, what would the alternative look like?

Johann Hari: So your ability to pay attention is intimately tied to the meaning you find in the thing you’re looking at. If you don’t find something meaningful, your attention will slip and slide off of it. As Professor Roy Baumeister said to me, a frog evolved to pay more attention to a fly than it does to a stone because the fly is meaningful to the frog and the stone is not, and what we’ve done is we’ve rebuilt our school system. We have stripped learning of meaning.

There was never a golden age, but we’ve made it even more about rote learning and completely meaningless tests. So I think we could really redesign the education system to infuse it with meaning. And I’ve seen places that did it. To give you an example, there’s a place called the Evangelista Shula’s Centrum in Berlin, a wonderful place I went to. What they do is at the start of each term, every class of kids chooses something they want to understand. So when I went there, the class I went into said they wanted to learn “Could humans live on the moon?”, and almost all of their lessons are then built around exploring different aspects of this question. The history class is about, okay, what’s the history of people going to the moon? The geography is like, well what could grow on the moon? The math is: okay, how do we design a rocket? You can see how that infuses education with meaning, and you could see how much better the kids attention was. So the school thing is huge.

I think there’s an even bigger element in relation to childhood. There’s a transformation in childhood. I almost think if you and I could go back in time and bring our great grandparents into the present, I think this is probably the change that would be most bizarre and alienating to them of all the changes that have occurred that are affecting our attention. So, I tell this story in the book through one of the great heroes that I met, a woman called Lenore Skenazy.

Lenore grew up in a suburb of Chicago in the 1960s and from when she was five years old, Lenore would walk out of her house and walked to school on her own. It was about 15 minutes away. When school ended, Lenore would leave and just wander around the neighborhood freely on her own. She would play games with the other kids that the kids would spontaneously organized, They’d run around and she would go home when she was hungry. That was how all childhood was essentially in the world at that point, with very few exceptions: Children played freely with other children without adult supervision. For most of time this was crucial for them. By the time Lenore was a parent in the 1990s, that had ended: she was expected to walk her kids to school, wait and watch them go through the door – even when they got pretty old – and to be there waiting at the gate to collect them at the end of the day. By 2003, only 10% of any American children ever played outdoors. So, essentially childhood became something that happened either behind closed doors or under tight adult supervision.

And it turns out there are loads of things in this enormous and unprecedented transformation in childhood that are important for attention. One, exercise. Kids who run around can play attention much better. The evidence for this is overwhelming. One of the single best things you can do for kids who can’t pay attention is let them go and run around. We have stopped that right, even before Covid, we stopped that and we imprisoned our children. In fact, the only place where our kids get to feel they’re roaming around at the moment is on Fortnite and on World of Warcraft – we can hardly be surprised that they become so obsessed with them. There are lots of other changes. Children learn when they play freely; what’s called intrinsic motivation. They discover meaning; this is absolutely essential for attention. Children learn through play, how to deploy attention – and it has to be free play. Just like processed food isn’t like food, supervised play where adults are telling kids what to do doesn’t give them the benefits of free play. So the reason Eleanor is the hero, one of the heroes of Stolen Focuses, not because she had this experience, but because of what she did with it. So Lenore was horrified by this change, right?

She could see that it was really harmful. And at first she tried to just persuade individual parents to let their kids play outside. She would often say to them, “What’s something you did when you were a kid that you really loved, that you don’t allow your own children to do?” And people’s eyes would light up. They talk about going into the woods, playing marbles, whatever it might be. But she realized, look, if you just try and persuade individuals, it doesn’t work. If you’re the only parent who sends your child out, they get frightened. You look crazy. In fact, often people call the police. So it just, it doesn’t work. So Eleanor now runs a group called Let Grow. And I really urge every parent grandparent listening to go to Let Grow dot org, and what they do is they go the whole schools and whole communities and persuade them to restore childhood together to let kids go out together on their own.

And I think of all the conversations I had with the book. I had so many moving conversations. I think the most moving was with a 14-year-old boy on Long Island. So I went to one of their Let Grow projects in Long Island And there was a 14-year-old boy. To give a sense of him, he was a big strapping 14-year-old, was bigger than me. His parents wouldn’t even let him go jogging around the block. I asked him why and he said, “My parents are frightened of all these kidnappings.” To give you a sense of this town, it’s a place where the French bakery is across the street from the olive oil store. His parents and him had a level of fear that would be appropriate if he lived in Medellin at the height of Pablo Escobar’s terror. Then Let Grow came along and he started to play outside his house, and he started to meet up with his friends. And what they’ve done just before I met him was they’d gone into the woods, and they built a fort as he talked. It was like watching a child come to life.

The joy of realizing he could do things, that he didn’t have to be constantly staring at screens, that he could go out into the world and explore it. Lenore was with me that day, and I remember when he left, she said think about all of human history. Young people throughout our history had to go out and explore. They had to map the territory they had to hunt. They had to find things. And then in one generation we took all that away and it had all sorts of stunting and warping effects on them, from their attention to their bodies. And that boy, given a little bit of freedom, what did he do? He went into the woods and he built a fort because this is so deep in us, this is such a deep human need. So the last quarter of the book is about children, because if we don't deal with kids’ attention, if they don’t form it when they’re young, they’re going to really struggle to develop it as they’re older, and this deadening school system and this home imprisonment makes them much easier prey for the invasive tech that we’ve alluded to.

That’s all for now. Hope you’re doing well. If you like this, please share it. We hope for a wide conversation here.

Cheers,

jep

Me Mom and Morgentaler

originally published at adifferentfish.substack.com

I was supposed to be aborted.

This was the core story of my life, as told to me from as early as I can remember. This didn’t happen in a creepy or abusive way – my mom was a physically battered person, having suffered traumatic, alienating pain as a child, tuberculosis as a teen, and ongoing emergencies and surgeries henceforth. The medical aspect of our story was something we always talked about.

So I grew up knowing that my mom had undergone serious surgery in 1969. Unbeknownst to the medical professionals, I was in there, dodging the scalpels and clamps, trying to look unsuspicious crouched against the womb wall. I succeeded; my mom discovered I was in there after the surgery. (I like to use this as a light defence of my inebriative tendencies. My early cells were bathed in morphine. My natural state, I brag lamely, is stoned.)

When the doctors found out, they instructed (demanded) my mom do the sensible thing and abort me on the odds. I was most certainly fucked, and carrying a baby would certainly fuck her body up even more. I’m sure they said this with the gentle courtesy and mindful respect male surgeons were known for in the era before married women were allowed their own bank accounts.

My mom wanted to be a mother in the most profound way. She was a proud, smart woman who by her early 20s had been bashed about by patriarchy to within an inch of losing it. She’d wanted to be a doctor; she wound up a secretary, putting my father through school so he could get his doctorate. She’d been body-shamed and class-shamed her whole life. She’d been present for the Blitz as a baby. She’d been molested and had never been helped with that. She’d gotten tuberculosis and had lived in a sanatorium for her teenage years. Then she’d married a robot, tricked him into having a baby with her (going off the pill secretly because she was lonely) (yes, she told us way too much, always) (no, none of the stuff we needed to know). Then she’d gotten sick again and had had her bladder removed, to be replaced with a rubber bag that always hung, mysterious and drying and smelling odd, in the washroom. Then me, the proposed abortion, and her heroic saving of my life. (If that sounds sarcastic, I don’t mean it that way.)

“No ruddy way,” she told me she had told them. I was her baby and she loved me. The doctors treated her like she was crazily irresponsible for making this decision, and treated her as a psycho throughout her pregnancy and delivery. She succeeded at bringing me into the world at great cost to her body. And here we were! I was lucky to be alive, and all children deserved to be safe from abortion. If I could have been aborted, who else was being cancelled in vitro? Could it be Jesus?

(Later I would learn that this effort had been harder for her than the heroic tale: after I was born, she fell into a massive depression. On top of that she needed more surgeries. We were not able to be close until I was about a year old. Cue issues: babies need their mom’s love in order to thrive.)

I know she told me this story to make me feel bold and powerful, to teach me that our actions speak most loudly, and that being alone with an opinion was not being wrong. We were all raised to be defiant, to be agitators, and to speak truth to power. I’m grateful for that gift: I like being this way. (I’m also grateful for her gift of life.) I also know that she told me the story so that she could feel less lonely: she overshared all my life, I think because she had very few friends. We were her garrison.

But I also know that I know that story because we talked so goddamned much, in my house, about abortion. Mom was a high-standing member of the Sarnia pro-life (in quotes) organization: she wrote the newsletter and sent it out, a la Phyllis Shlaffly, and went to marches and demonstrations. We kids were part of it; we paraded slowly around the dining room table every month or two in a collation parade: pick up each sheet in order, tamp the stack flat, staple. It was fun. Working with your family is fun.

It was also GROSS. I joke to dark-humoured friends that I knew what dismembered fetuses looked like before I knew where babies came from, and it is true. Posters and photos of shredded babies in garbage cans were all over the place when we worked. Ironically, we were not allowed to watch Happy Days because it was too adult. People are strange.

It was also GROSS. I joke to dark-humoured friends that I knew what dismembered fetuses looked like before I knew where babies came from, and it is true. Posters and photos of shredded babies in garbage cans were all over the place when we worked. Ironically, we were not allowed to watch Happy Days because it was too adult. People are strange.

Ruh-Roh

This was a core part of my life until sometime in the middle of high school. High school is, if you’re doing it right, when you start to disassemble 2D ideas, right? On the surface, the argument presented by pro-life advocates is hard to refute: killing babies IS terrible.

But that two-dimensional presentation doesn’t bear scrutiny. The giant issue of patriarchal oppression is not mentioned. The human rights question of bodily autonomy is avoided, except for the one that says fetuses have a right to life. Simplistic ideas shouldn’t sway grown adult people, but they do, especially if they’re paired with simplistic religion and reduced completely to emotions. Right-wing ideas tend, in my experience, to lack nuance because right-wing people tend, in my experience, to lack imagination and not know it.

So in high school I befriended females, and learned the non-theoretical issues of pregnancy and abortion from their perspective. My first pro-choice act was to ask for a meeting with the principal over a student-made anti-abortion poster that had offended me in the hall. I took it down and showed him: a Bristol-board drawing of a woman in a Canadian flag dress, holding the rope of a huge guillotine next to a big, bloody basket of baby heads. “Can you imagine how seeing this would feel to any student who’d had an abortion?” I asked him. “To see herself called a murderer?”

“There are girls here who’ve had abortions?!” he asked, shocked. We were a school of two thousand teenagers. Stupidity is maintained purposefully, to preserve illusion, to maintain power.

When I moved away for university, I became more firmly convinced that – whatever its issues – abortion was for women to make decisions about. A girlfriend schooled me in the on-the-ground facts of abortion, and an essay in my intro to philosophy course gave ethical clarity to the idea. I never told my mom that I was now completely pro-choice, although it came out sideways in conversations over time, and got bundled into the many ways I offended my mom as an adult.

Radical Christians Are Intentionally Stupid

This American disaster, this plot to dehumanize women, has me thinking a lot; I know it has my brother thinking a lot, too. Mom died in 2019, and I don’t want to think about what she’d think, because I am afraid she’d have been happy, and that would be hard.

My mother was complicated. She was hurt in many ways, and she hurt people, too, in the powerful, powerless way Margaret Atwood describes in Surfacing:

I have to recant, give up the old belief that I am powerless and because of it nothing I can do will ever hurt anyone.

She was judgemental and moralistic (so am I). But if she had been given a wand and a wish, I promise you she would have arranged for all the potential babies in the world to be born and then cared for and loved and nurtured by that whole world. She would have wanted that for everyone. She was the kind of woman who took pregnant teens into her house and who gave her money away to anyone who needed it, who treated people, unreservedly, with basic respect and dignity. None of the people rolling back women’s rights in the USA can claim any of that.

But it’s a silly wish. I like to consider reality and make plans that can work. Step one of eradicating abortion can’t be “first, have all the babies.” Being coy or simplistic about the facts won’t help anybody solve anything. Like giving birth to a child, abortion is a powerful act, and – this is the most important part, the part my mom left out of the moral equation – the decision to choose is complicated by everything in the world: by biography, geography, religion, biology, sexuality, class, race, inclination, health, temperament, social pressure, opportunity, etc. So the only people who can decide are the actually pregnant people, because the whole complicated situation exists inside their actual bodies. Who else could choose? Only under a patriarchy could that be challenged, and the challenge is necessarily a stupid one, one that cannot entertain or consider any facts or details of human complications after their short, certain answer. Drawing a line past which you will not think is a special kind of stupidity, a gleeful stupidity.

What has the Christian Right done in America since you first heard of it? Attack schools and teachers and new ideas, undermine science, undermine “facts” in general, oppose effective government. They’re superstitious AF – it hurt my brain to hear Mike Pence talk last week about his “someday in heaven” fantasy – and they ban books they don’t understand. They believe in the actual Devil, even as they spread suffering. Stupid is the point, because it’s so disablingly effective. Once nothing about America works, the power vacuum they’re setting up will be filled with only the supposedly best people, the most honest and honourable – Brett, say, or Amy, or Clarence – who will after that, wait like dour little medieval crows for the end the world. SUPER.

I recall a conversation in my 20s where I confidently claimed that certain gains could not be reversed anymore. I was at at restaurant named KOS on College Street in Toronto, with my friend Adam. I think about it all the time now, how a lot of what we thought was done – achieved – has been dismantled in a slow, sneaky, 40-year scheme. I thought then that progress was just progress, not an endless fight for it. But it turns out that people without souls will do anything for power and money. I for one want to stop feeling surprised. I get it. I get it. I get it. Dang.

Should my mother have had an abortion? Should my status as an abortion survivor inform my opinion on what women can do with their bodies? That’s the hook on this piece, right? I’m living the “What if?” comic of my life. I wasn’t aborted, and I came close, and so what does that say?

Nothing much.

It says life is complicated, choices have effects, and drawing hard lines around things is different – and less important – than taking stands.

I hope my mom would have seen the protests, heard the stories, witnessed the experiences of so many betrayed women this week. I hope she could have seen Amy or Clarence as the horrible traitors of Gilead they clearly are. I hope she would have witnessed the actual whole story last week in America, and found some nuance. But who knows? The blessing of death is that, after it, one is removed from hypothetical equations. I was glad she missed COVID, which she missed by a year, and I guess I’m glad she missed this.

I hope for this clear affront to women and the world to be a blip, something that is counteracted by responsible adults. That’s not looking likely, but I hope.

Thanks for reading.

Teaching Film 07: Children of Men (A Different Fish)

A kind of skimpy little article about teaching Children of Men in HS film studies. Published at A Different Fish.

Here Comes The Sun King

June 2022, digital photos and fuckery

At least we’ll always have FACEBOOK! HAHAHAHA

Read MoreCells

From about 5 years back. I’d forgotten about these.

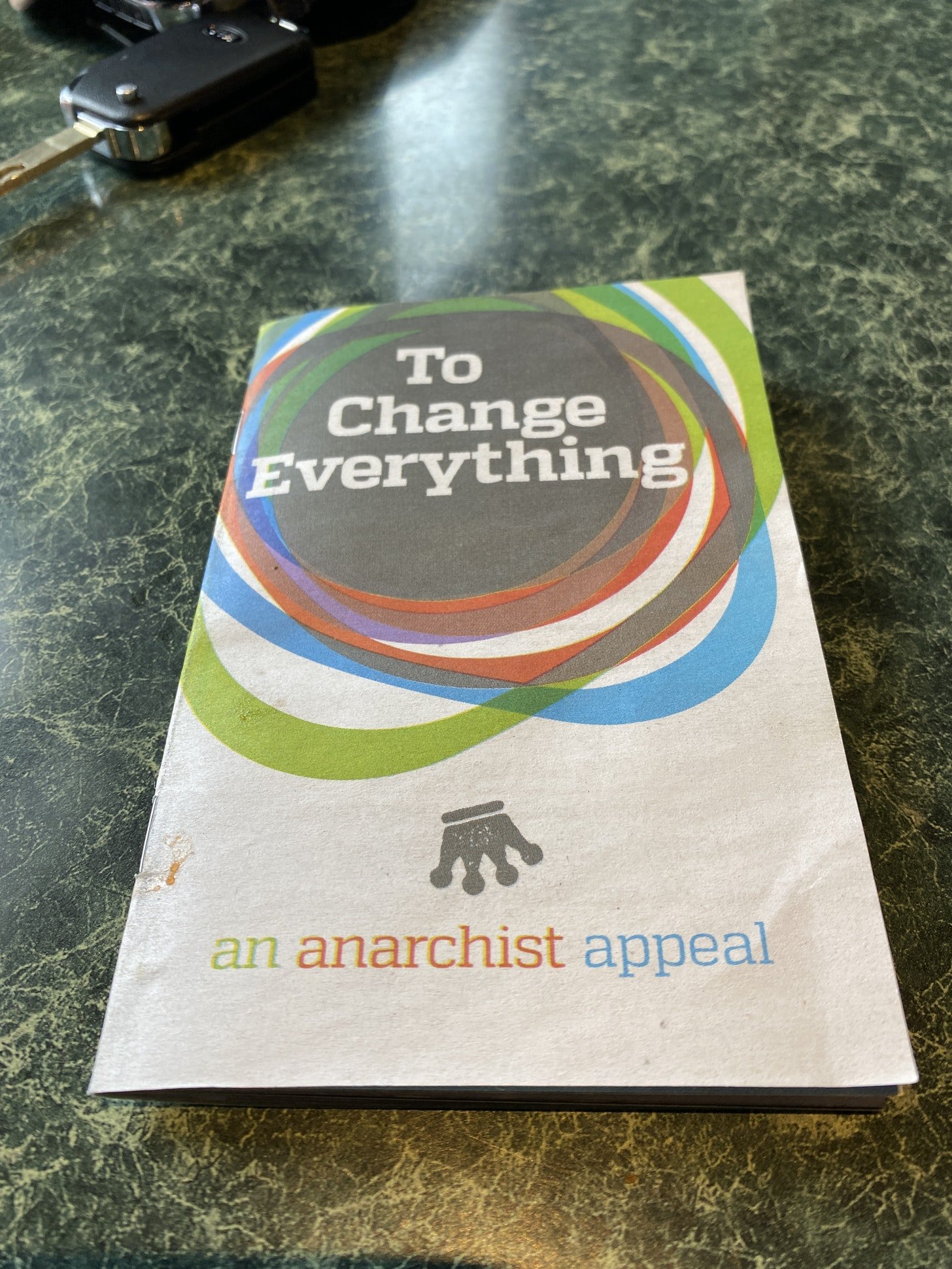

Anarchy in Middle Age →

Have I found a group I can get along with???

In grade 9 a friend showed me the “anarchy” symbol – it was probably on his jacket –and he explained that it meant “no authority.” That appealed to me a lot: I took to drawing and thinking about it, wondering why we DID have authorities. I thought people could do better if they were unrestrained. (Thought in a grade 9 way.)

At some point, the friend saw my stylized anarchy logo and corrected my explanation – a clear misapprehension of the concept. It’s not a utopian idea, he said (in a grade 9 way); it’s graffiti, it’s tough and angry. He was a poseur of the first order,* but what did I know? I moved away from the idea and the symbol, and he arranged it aesthetically among the badges on his jacket.

*I’m not judging his grade 9 self – god forbid. He remained this way forever, and never met anything he didn’t want to pose next to. Some people are like that.

The Right to Coerce?

About three decades later, I would revisit my position again after watching an interview with Noam Chomsky, whom I love a lot. In it he described himself as “essentially an anarchist,” and defined it as a belief that all coercion needed to be justifiable and justified to be valid. I don’t have the exact quote; it was a long time ago. That’s what I took away from it, and I felt really grateful for the idea, which put words on my own unnamed, lifelong position against dumb authority.

If I’d been instinctively rebellious as a teen, in my 20s (and on) I sought order, sought legitimate ideas that helped me make sense of the world. I gathered them like nuts in the forest, incorporating good explanations into my life and mind. (I am a messy person with high philosophical and emotional demands, and so did not thrive in the footnote scenario of university. Looking for the exact quote is a distraction – I’m trying to tell you something here, I would think. I still do. Apologies.)

“All coercion must be justified” settled in along with “Mean people suck,” which I’d gotten from a sticker, and “You are responsible for this one life you have,” which I’d gotten from Sartre, and “Kids don’t need to be bossed around constantly” from a Native American literature class in uni. I’ve never actually written them down as I’m doing right now – I should do that sometime.

Anarchist!

So am I an anarchist? I started to wonder. I am not a joiner by any stretch. To truncate a Marx quote: I wouldn’t want to belong to any club. I’ve always found social pressure (usually to conform) annoying. I have a nice, scattered, particular social group that I mostly see one on one. I don’t play team sports. I’m not mean about it – I’m just this way. So I had no interest in looking for an “anarchist” community to explore, and didn’t care what other people who might be anarchists thought. I tucked the idea away.

Then, last month, I was in San Francisco with Marjan, walking around in the Haight-Ashbury area, and found Bound Together, an Anarchist Collective Bookstore, all black and dusty, filled with shelves of books, zines, T-shirts and pamphlets and stickers and posters. Every one of them I agreed with. They were all concerned with big things – saving the planet, undoing the extractive system, solving racism, helping kids. I couldn’t buy any more books – I’m travelling and have already picked up too many – but we bought a couple of little zines and pamphlets in the twice-folded paper format. One I haven’t read yet was about Iran’s recent history; the other I have read, and it is why I’m writing this.

I have long considered creating the little book I needed when I was a teen – advice about how to survive and thrive, what to expect from adulthood, how to know what was right and wrong. I draft it all the time. I’m currently working on one about how to manage the feelings and situations of climate change. I never finish these – they seem too big, too easily bad, and I’m a person without authority, with no mentionable letters after my name. I’m not worthy, etc.

But this zine had great advice out the wazoo! It’s called To Change Everything: An Anarchist Appeal. It is the creation of a collective called CrimethInc., “An international network of aspiring revolutionaries.”

It is a quick read, very clearly and practically written, and it dives immediately into the meat of things (bad mental image). Every second page is a new chapter, so that if one were in a hurry, one could flip through the title pages and get the entire idea, in bullets.

Here is that whole list:

To change anything, start anywhere

Start with self-determination

Start by answering to ourselves

Start by seeking power, not authority

Start with relationships built on trust

Start by reconciling the individual and the whole

Start with the liberation of desire

Start with revolt

The problem is control

The problem is hierarchy

The problem is borders

The problem is representation

The problem is leaders

The problem is government

The problem is profit

The problem is property

The accompanying pages have maybe a hundred words each, but they explain the big ideas well. The last chapter has this title, which is very compelling: “The last crime.” It asks the reader to envision the next thing, the thing after this. And there’s a short glossy page describing the terms Anarchy, Anarchism and Anarchists. Anarchy is:

what happens wherever order is not imposed by force. It is freedom: the process of continually reinventing ourselves and our relationships.

Any freely occurring process or phenomenon – a rain-forest, a circle of friends, your own body – is an anarchic harmony that persists through constant change. Top-down control, on the other hand, can only be maintained by constraint or coercion: the precarious discipline of the high-school detention room, the factory farm in which pesticides and herbicides defend sterile rows of genetically modified corn, the fragile hegemony of a superpower.

You’ll have to trust me to be honest here (but I suppose that is always true): I neverread philosophical treatises without a litany of complaints. I’m an almost hostilereader when it comes to worldviews or strategies. But with this little book, I have nothing to object to. I read it fast and exclaimed to Marjan, “This is AWESOME. I love this!” I’ve been thinking about it all month. I feel totally inspired by it.

Note: The whole thing is yours for free at tochangeeverything.com. I’m considering getting a bunch of paper copies to give friends (available for the cost of postage – I love it).

Fake Humanist

I lied: I did sort of secretly “join” a group called “Humanists” after learning about it, after finding out Kurt Vonnegut was a member (maybe the head at one point?). I never bought a book about it, though, and never looked up a website. Their basic idea just made sense, and I loosely flirted with adopting the label. (Nobody ever asks you, do they, so I never had to really say “I’m a humanist.”)

But maybe I’m an anarchist? I’ve gleaned over the years that Anarchism had been a legitimate cause for a lot of leftie intellectuals in the first part of the 1900s, and that they’d been written out of the conversation at some point. It feels funny to think about after this much time. It feels nice to learn that me and my grade 9 self share something in the values department. But in the end, it won’t make much of a difference either way.

I think I’ll try and finish the “Guide to This Climate Change Shit” thing for kids, and I think I might not give any thought to whether anybody reads it, and not worry about clicks or likes or shares or impressions – I’ll just print it, staple it, and send some copies to Bound Together and call that good enough. The ideas we can live on spread by luck and love as much as they spread by intention.

***

Note: You can find my comic meditation on climate change (2019) at Bound Together, an Anarchist Collective Bookstore in San Francisco.

And: Just coincidentally, an Anarchist coffee shop just opened in Toronto, on Jarvis. I look forward to visiting!

All for now. Hope you’re great. Spring is here!

love

jep

TREES

This might be a series.

Uh Oh! It's the Devil!

It was a normal day but not for long.

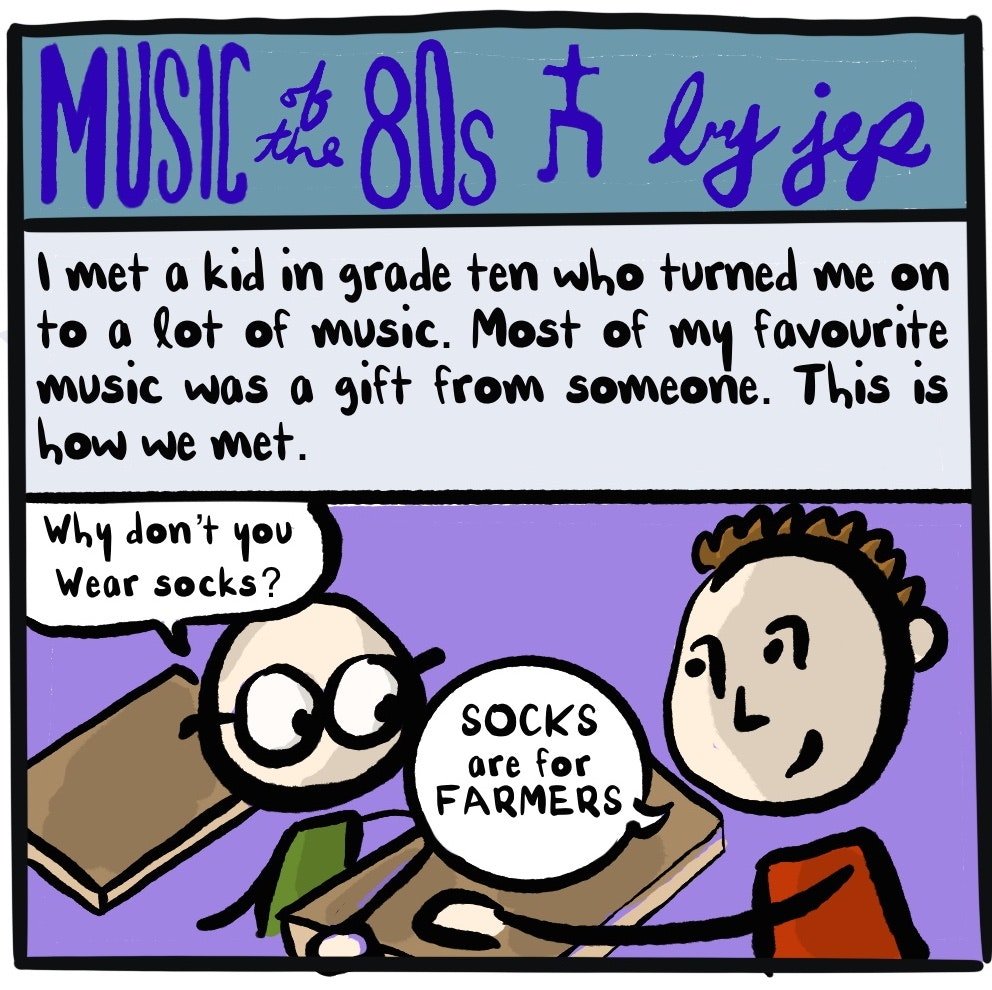

Read MoreMusic of the 80s, #61: Socks Are for Farmers →

An ode to an old friend and his excellent musical suggestions - at my comics newsletter Music of the 80s. Clicking the link will take you to the whole thing (8 panels and some videos and related thoughts.)

La Brea.

Photos and fuckery. May 2022.

True.

originally published in an edition of the misterjep.substack.com newsletter

Celebrating Autism isn't Uncomplicated →

This was originally posted at adifferentfish.substack.com

I love this speech, and love this person (Amethyst Shrader, Autistic Activist.

“Tolerance” is the barest of minimums. Celebration can’t just celebrate the bits of autism that can serve capitalism. Love the whole person as they are.

a selfie

Done with Facebook

I am here to report that quitting Facebook is as difficult as quitting smoking. I haven’t had a cigarette in 12 years, but I recognize this bullshit: the vow, the reconsideration, the half-measures, the baby steps. I quit smoking about 300 times before it stuck, and it took something bigger than me to do that. With smokes, it was my beautiful cat Jack dying of cancer (he did not smoke). His protracted illness pushed me to full-time smoking again, a major step back, and I told my partner “I need this, one more time. Let me smoke until it’s over, and I’ll stop forever.” I smoked my last butt as I cried and buried my boy in the backyard. And that was it.

Facebook was just entering my life around then. I was suspicious of it, but liked the idea of being findable, easily, by former students and old enemies. I bought into it, really, when my good friend Derek died suddenly: the collective mourning (he was very loved) happened on Facebook - the sharing of memories and coordination of memorials - and it was very powerful. “This is something real,” I thought, and mostly surrendered.

It was never an easy relationship, but it was very full. I did in fact regain contact with old friends and students, and restarted relationships with family I didn’t see offline. I don’t remember when FB started to really sour, but it did, as we all know, and I tried leaving - for a year at one point. It was important in both causing and grieving the sham presidency of *45. It was important to me in allowing a forum to share the comics I was making - for a time FB was the only place I was publishing them.

But it has sucked for a while. At one point, inspired by Hank Green’s “it’s a baby” post, I thought I should stick with it and watch it evolve into its next phase. But as friends have either left the platform or gone silent, I have found it both empty and irritating - and, with Fuckerberg’s obnoxious dodging of scrutiny by changing its name to Meta, gross.

I still kept going - but last week a stubborn battle that has been rolling for years came to a head: Facebook continually asking me for my phone number “for my own security” had been pissing me off for years, but I just ignored it. Now they’re sending me notes telling me I’ll lose access if I don’t comply. To be clear: my phone number is NOT a secret. It’s all over the place. But the strong-arming, and the lying about why - they turned out to be the last straw. I’m going to not comply, and I will be locked out until I comply, on May 19th.

It’s good. I needed something to push me off. I don’t like moral grey areas - I like to take stands - and facebook made everything grey. I am taking the same opportunity to leave Twitter, and to at least temporarily stop reading the news. (I will keep Insta if they don’t force my hand there - I am not addicted to it, and do still think it’s a positive space.) I want to wake up in the morning and just be, and decide for myself what I will pay attention to.

I’m posting my email and phone and address in my FB profile banner, so that if anyone really needs to reach me, they’ll be able to. I don’t know what will come next. I miss Web 1.0, to be honest. I miss a lot of stuff. But I’m really, really genuinely tired of having antagonistic relationships with companies and products that seem to hate me - Mac, FB, google. I want to withdraw, as much as possible.

I’m not posting this on Facebook - I don’t care to hear the mocking that comes with that. I’ll join the next good, well-populated, non-sociopathic social media phenomenon, after a good period of watching other people try it. Mostly I hope to spend more time reading. :)